What is Sciatica?

Sciatica is poorly defined but could be loosely defined by pain originating around your lower back area and traveling down (radiating) into your lower leg. As with most pain, everyone’s experience is different. For example, some people have herniated discs, spinal stenosis, or osteoarthritis and don’t have any pain, while other people have the same condition and have severe pain. Pain is affected by many things – which is a good thing. That’s means we can do many things to help.

Why is it happening to me?

Sciatica is quite common with almost 50% of all people experiencing sciatic-like symptoms in their lifetime. It is likely due to a combination of things from arthritis, nerve root compression or irritation, your stress level, fear of movement, sense of control, sleep, current physical capacity, uncontrolled comorbidities (high blood pressure, elevated blood sugars, obesity, etc.), or maybe a congenital condition. I tend to operate by these rules: was there a recent event that started the pain? Are there symptoms that stretch beyond pain (loss of bladder or bowel function, fever, dyspnea, odd lumps somewhere, or unexplained weight loss)? Are the symptoms getting progressively worse? If the answer to one or more of those questions is yes, then you should probably get your Sciatic pain checked out. However, I find, in the clinical population I work with, that it is normally chronic, intermittent, and not associated with other more serious symptoms.

Should I be worried?

If you don’t have the symptoms listed above, then there is likely nothing to be immediately concerned about. However, having chronic pain that affects your quality-of-life is depressing. But you can do something about it.

What can I do about it?

There is evidence that in acute injuries (think car accident) surgery is beneficial. However, with chronic pain it’s a bit more complicated. It appears that surgical interventions compared to non-surgical management fare about the same on average when looking long-term. Conservative management is all about getting all your risk factors under control and engaging in activities that are specific to sciatic pain that will likely reduce sensitivity, reduce fear, improve musculotendinous and ligamental structures, and maybe neuromuscular improvements that account for some of the benefits seen.

Risk factor control (just some)

Below are just some risk factors that everyone, but especially those who want to help better manage their pain, need to try to achieve. Controlling these markers are associated with less pain and better health overall.

- Obesity (Waist or BMI) – Waist: men <40’’ and women <35’’.

- Blood Pressure: <120/60 (<130/60 w/ Diabetes).

- Diabetes: fasting blood sugar <130 and 1-2 hours after eating blood sugar <180.

- Poor Sleep: get 7-9hr/night, wear your CPAP, investigate sleep hygiene habits.

- Cholesterol: LDL <70, HDL >60, talk to your doctor about medicines.

- Activity: 3500-7500 steps/day (be active)

- Aerobic Exercise: 150-300 minutes/wk. of “somewhat hard” walking, biking, dancing, etc.

- Resistance Exercise: 2-3d/wk. of “somewhat hard” resistance exercises that work all your muscle – doing pushing, pulling, hip and knee bending, and trunk moving.

- Nutrition: Eat a healthy number of calories for your weight, eat 30+ grams of fiber daily, ~ 0.7-1.6g/lb. of healthy body weight, <6% of calories coming from saturated fats, and less than 10% of your calories coming from added sugars.

Specific Sciatic Pain Exercises

You must get into a place where your pain is manageable. Expecting increased movement to decrease your pain immediately is unreasonable. The process is…well, a process. So, if you’re in severe pain often try to cut back on some of your more demanding tasks that engage your back and hip muscles, and work on managing those risk factors as best as you can. If you’re in severe sciatic pain and not doing any physical interventions to help it then maybe just stretching and range of motion type exercises would be a good place to start with the acknowledgement that more specific and general strengthening exercises are coming.

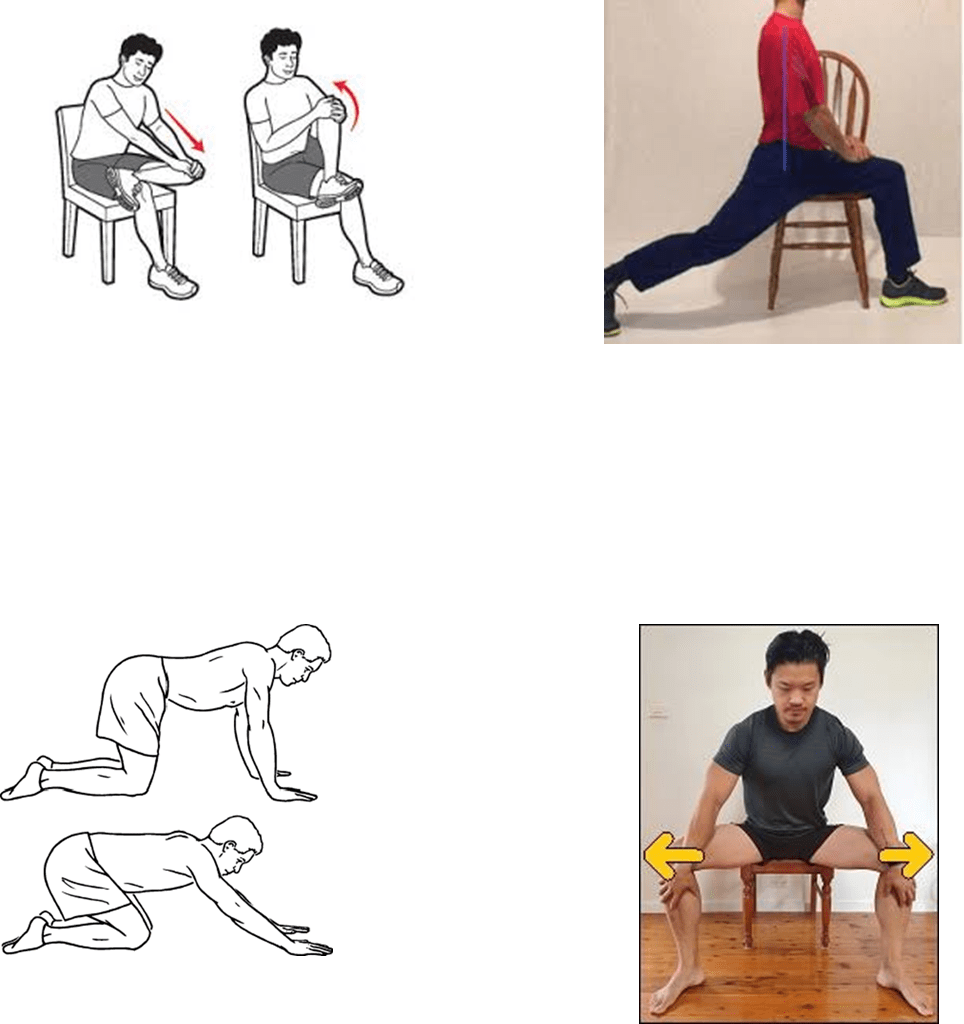

Stretches

A great place to start, especially for those people whose pain is quite severe. Aim to stretch every day, then 2 or 3 times per day, incorporating stretches that move the hip in its various ways of moving. Progress quickly into other exercises as able. (See below)

Specific Resistance Exercises

Generally, I start with isolation type exercises that aren’t too demanding, lighter loads and higher repetitions, reasonable RIR, and a clear pain threshold depending on the person’s starting pain that day and average pain. I add more exercises as able but am always trying to ditch these exercises for more compound less-specific exercises as someone’s pain gets more tolerable.

Here Are Some Examples

- Standing abduction (cable, no weight, ankle weight)

- Machine abduction

- Lying single leg raises with other foot on floor – alternating sides

- Bird-Dog Hold, Modified plank hold, or dead bug hold

- Machine kick-back (or cable, ankle weight, banded, etc.)

- Lunges (reverse, assisted, weighted, curtsy, forward, etc.)

- Single leg Bridge (hip extension) – alternating sides

- General Strength and Conditioning Exercises

As stated above, low aerobic capacity, low muscle mass, being sedentary are all risk factors and it appears that the more capable a person gets the more resilient they are to pain. So, a goal is always to improve our aerobic capacity and overall muscle mass and strength. This topic is discussed in length elsewhere, so I won’t elaborate here.

An Example of this in Practice

Week 1:

Modify as many uncontrolled risk factors as possible (better sleep, better BP, better DM2 management, implementing relaxation/prayer for anxiety, counseling for depression, etc.); then, modify some exercise they are currently doing to decrease mechanical loading/stress on lower back and hip muscles, get rid of some exercises to decrease global stress, add in the stretches (all four) listed above and have the patient perform them 2 times daily for 1-2 minutes each. Add 3 “sciatic specific”, not to demanding, exercises for their back and hip musculature on differing days in combination with other general strength exercises they were doing already. Make it simple and accessible. Make it at a lower intensity with higher rep ranges (RIR 4-6 at ~50% 1-RM). Encourage the person to walk 5-7 days per week for 20-minutes a day at a “fairly light” intensity.

Week 2:

Assess pain – modify program as needed: Patient states pain slightly better, continue stretching, and start to increase sets (volume) on specific hip and back musculature exercises, keeping the intensity and reps the same.

Week 3:

Assess pain – modify program as needed: Patient states pain hasn’t gotten better or worse but is walking more now. Continuing with plan, continue to increase volume as able until the patient is doing ~8-12 sets/week/major muscle group for their general strengthening exercises and are tolerating about the same volume for their specific back and hip exercises.

Week 5:

Assess pain – modify program as needed: Patient met volume, feels good. Start to decrease their RIR to 2-4 and bring their intensity up (60-75%) and their repetitions down (~6-12) gradually over 2 weeks as tolerated.

Week 7:

Assess pain – modify program as needed: Continue with this intensity if able and now trade 1 “easier” isolation back and hip exercise for a more compound, yet specific, exercise. An example, a bird dog for a lying single leg raises (more ROM and less assistance) or trade the abductor machine for a curtsey or lateral lunge (greater musculature involved, more demanding).

Week 8-12:

Assess pain – modify program as needed: Continue to trade easier specific exercise for more general compound exercise until the person has adopted a traditional resistance training program. I find that some people enjoy keeping a few specific isolation exercises (like the abductor or kickbacks) and I never discourage keeping them but don’t track their progress like I do on a compound exercise. Try different compound exercises, different aerobic modes, and various stretching throughout macrocycles to always have a good “diversified exercise portfolio.”

Firstly, this is an expediated program example, I find that significant reductions in pain can take 6 months to come to fruition. Patience and appropriate modification are key. When someone’s pain increases, their quality of life starts to dip, or they cannot perform some of their daily tasks like they used to, that is a good sign that they are “overshooting” their resources for recovery and/or their movement tolerance at that time under their current life circumstances. I find most people will have to decrease some intensity on some specific exercises but are almost always able to get back to that intensity and then increase said intensity over time.