Exercise! How much, how hard should it be, what should I do, what machine gets rid of my belly (while person shakes their belly)? These are just a few of the most common questions I have received in my many years in the fitness industry. Perhaps one day Ill write an article about the craziest questions and have a good laugh. I’ll start by trying to simplify “Exercise” by breaking it into three parts: cardiovascular, resistance, and flexibility. Each separate part has its own nuances, considerations, and recommendations. Firstly, I want to say that before you start any new physical activity regimen it’s a good idea to complete a PAR-Q, which is a questionnaire to access how “ready” you are to start exercising, or talk to your primary care physician about your plans. You can even take this article to them.

So, the question this article addresses is “how much “cardio” do I need to do for general health? This is a common question I receive from clients and patients. Cardiovascular exercise has a plethora of health benefits ranging from cardiovascular improvements, mental health improvements, risk factor reduction, muscular improvements, and the list goes on. An individual who does an adequate amount of cardiovascular exercise weekly will experience a significant mortality reduction; some research demonstrates over 30%. Before getting into the details of what a cardiovascular exercise routine should include for people whose goal is general health it is important to mention that an exercise regimen for general health, but really for any goal I can think of, would be inadequate without both cardiovascular and resistance training. However, for the sake of simplicity I will devote two separate articles to cardiovascular and resistance training for general health.

When explaining how to construct a cardiovascular exercise routine to clients or patients I usually start by explaining that activity and cardiovascular exercise, while similar and have some crossover, are not the same. Activity, as I define it, is unstructured movement that doesn’t hold any intended purpose as it relates to fitness. Examples of activity include yard work, walking around the store, carrying in the groceries, and even fidgeting at your work desk. Generally, there isn’t any structure, you’re just getting the groceries in the house and not thinking about much else. Cardiovascular exercise is more structured and generally there at least a broad goal in mind. Walking on the treadmill 30-minutes today so you can improve your chances of weight loss, doing a 45-minute biking routine so you can improve your biking performance, or walking 15-minutes during lunch at a “somewhat hard” pace to improve your health would be some examples of cardiovascular exercise. While different, we need both. Studies have shown that people who are active and perform cardiovascular exercise tend to be healthier on average than those who only check one of those boxes.

Because of the diverse nature of “activity”, it is quite hard to say precisely how active someone is, but to make life a little easier researchers look at people’s steps per day (steps/d) to define how active they are. While this doesn’t give a 100% accurate representation of someone’s activity, it is a great correlative. Many studies have looked at people’s risk associated with their steps per day trying to answer the question, how many steps/d does a person have to take to receive all the benefits? The results from these studies are wildly diverse, ranging from 3,500 steps/d to 10,000 steps/d. However, a common theme among these studies is that people who were more active tended to have better health (less comorbidities, lived longer, less risk of disability, etc.) than their less-active comrades. My recommendation to clients and patients is, depending on their current activity level, capacity, and lifestyle factors; is to try to get between 3500 – 7500 steps/d. and if you can increase beyond that with no negative interference to your life (time with family, soreness, work time, fatigue, etc.) then be my guest!

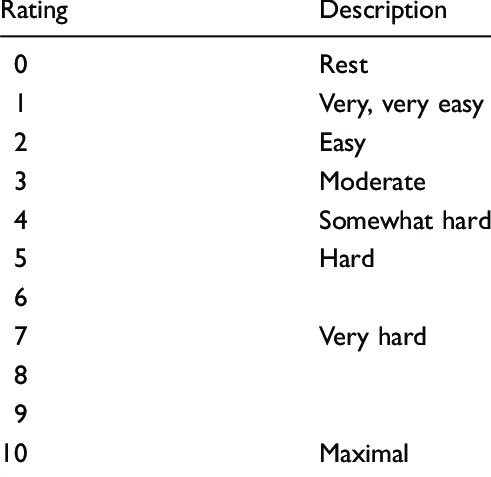

Cardiovascular exercise (also referred as aerobic exercise or conditioning) can be simply defined as an activity that gets your heart rate up and keeps it up. Examples could include cycling, walking, running, rowing (machine or actual boat), tennis, dancing, snow shoeing, and the list goes on. Often you will hear words like “continuous” and “rhythmic” when you read about attributes of cardiovascular exercise; because if an activity meets those criteria, it will likely be good at keeping your heart rate up. I tend to push people toward cardiovascular exercises that they enjoy, have access to, and do not give them too much discomfort. For example, if someone doesn’t have access to a treadmill, gets pain in their knees on the treadmill, and dislikes the treadmill, then the treadmill is likely not going to be a good option for a cardiovascular exercise modality. However, if someone has a friend who plays pick up racquetball at a club, the person is a member of the club, they like racquetball, and tolerate it well, then racquetball would be a great choice for this person. So, how much of that stuff do you need to be doing for general health? We all need to be participating in at least 75 -150min/week of vigorous exercise or 150-300 minutes a week of moderate exercise. The terms “moderate” and “vigorous” refer to how tough the exercise is, but how do we decipher what is light, moderate, or vigorous? Well, a lot of ways: Mets, Watts, subjective intensity, heart rate, and even an assessment of ones talking capabilities. However, I think the most useful and simplest is one’s subjective intensity, or how hard you feel the exercise is. The idea behind subjective intensity is that you would use a scale, either in your mind or in front of you, to assess how hard the exercise is, and trying to stay within a certain range. There are various scales but the two most common are the 0-10 scale (CR-10) and the 6-20 “BORG” scale. I tend to use the 6-20 BORG scale for clients and patients when determining how difficult their cardiovascular training is, but I don’t think it matters too much if you use the same scale every time. Moderate intensity would be a rating of ~12-13 on the BORG scale and vigorous intensity would be a rating of ~15-16 on the BORG scale. So, when prescribing someone, or yourself, a cardiovascular exercise regimen for general health you should think about what would be best to do, how hard is that going to be using our subjective ratings of intensity scales (moderate? Vigorous?), and then start at the bottom of the recommendation for that intensity and work your way up to the latter end taking account of not only subjective rating during the activity but also subjective rating throughout the week to decide when to increase your minutes per week. Below is an example of how I might set someone up with a cardiovascular regimen for general health and their progress.

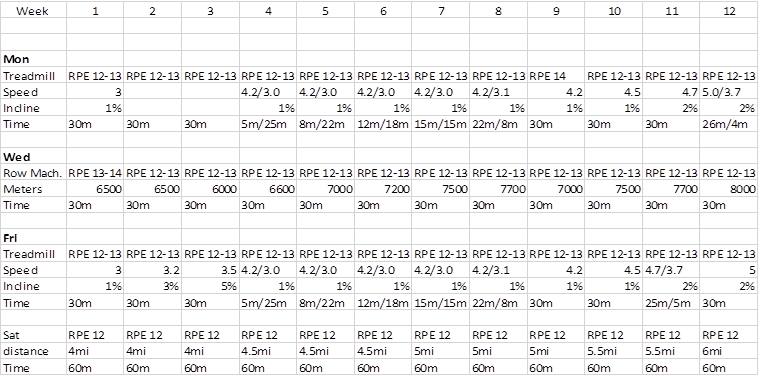

Example: Scott is 40 and wants to improve his health after going to his MD and getting a recommendation to start being more physically active. He is sedentary and has been for the past 15 or so years, outside of his daily tasks including yard and housework, with a history of walking, running, and sports in high school. Scott is motivated after his visit with his MD and recently got a membership at a local fitness facility. He expounds on his schedule and decides that he can commit to going to the fitness facility ~60 minutes 3 days per week (Monday, Wednesday, Friday) and walk on Saturday morning with his wife for about an hour. He also states that he enjoyed running/walking on the treadmill many years ago and wants to get back to that, he is not interested in recreational activities, and is not opposed to other modes such as biking or rowing. Using this information Scotts plan is to do 30 minutes of aerobic exercise using the treadmill and row machine on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at the fitness facility and walk with his wife Saturday mornings for 60-minutes all at an ~RPE 12-13 (that’s 150 minutes/week of moderate aerobic exercise). As he gets more fit, he must increase his intensity to maintain that same RPE range, and even starts to run around week 4. His 3-month progress is below (Scott also plans to resistance train on those days as well but is not shown here).